American West in pictures, 1860s-1870s

In the 1860s and 1870s, photographer Timothy O’Sullivan created some of the best-known images in American History. After covering the U.S. Civil War, O’Sullivan was the official photographer on the United States Geological Exploration of the Fortieth Parallel under Clarence King, an expedition organized by the federal government to help document the new frontiers in the American West. The expedition began at Virginia City, Nevada, where he photographed the mines, and worked eastward. His job was to photograph the West to attract settlers. In so doing, he became one of the pioneers in the field of geophotography.

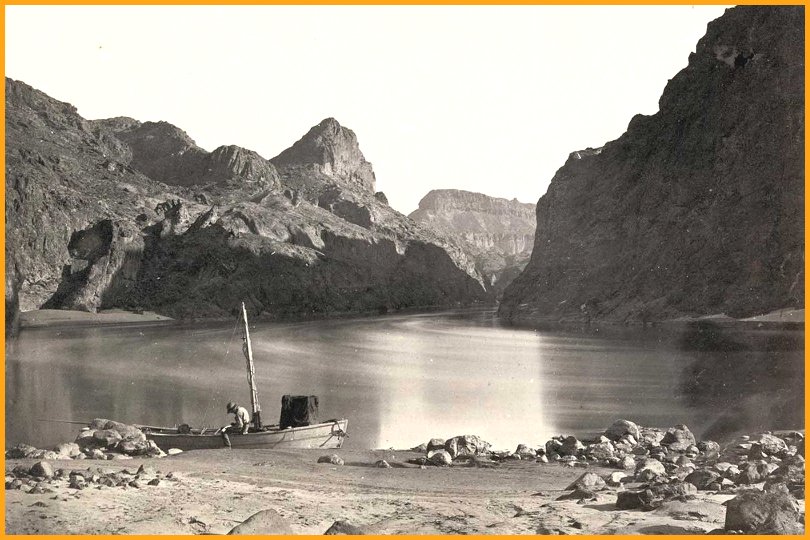

A man sits in a wooden boat with a mast on the edge of the Colorado River in the Black Canyon, Mojave County, Arizona. At this time, photographer Timothy O’Sullivan was working as a military photographer, for Lt. George Montague Wheeler’s U.S. Geographical Surveys West of the One Hundredth Meridian. Photo taken in 1871, from expedition camp 8, looking upstream.

O’Sullivan’s pictures were among the first to record the prehistoric ruins, Navajo weavers, and pueblo villages of the Southwest. In contrast to the Asian and Eastern landscape fronts, the subject matter he focused on was a new concept. It involved taking pictures of nature as an untamed, pre-industrialized land without the use of landscape painting conventions. O’Sullivan Above all, O’Sullivan captured, for the first time on film, the natural beauty of the American West.

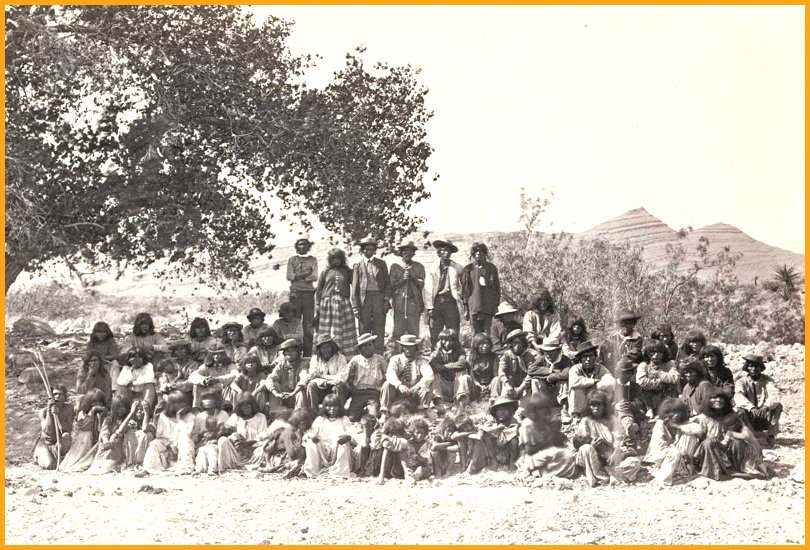

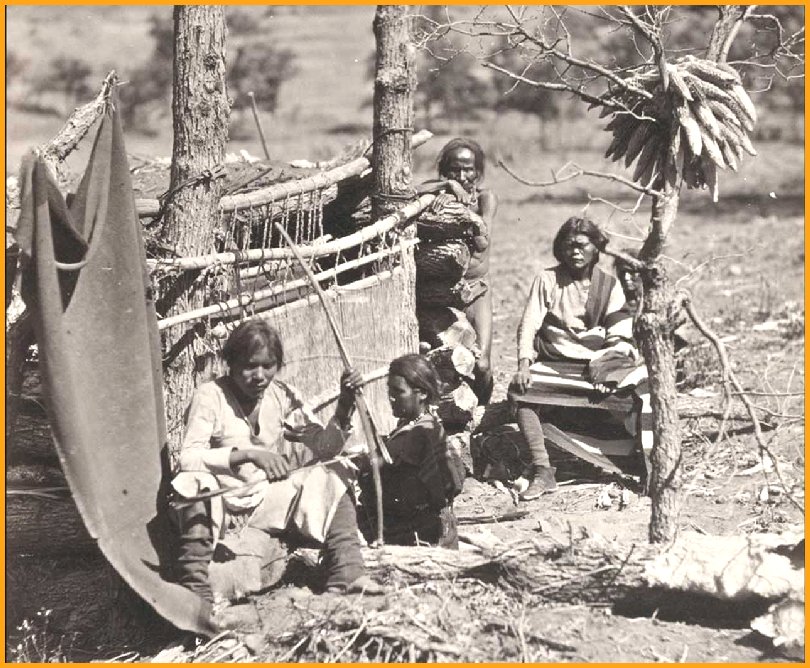

Pah-Ute (Paiute) Indian group, near Cedar, Utah, in 1872.

The completion of the railroads to the West following the Civil War opened up vast areas of the region to settlement and economic development. White settlers from the East poured across the Mississippi to mine, farm, and ranch. African-American settlers also came West from the Deep South, convinced by promoters of all-black Western towns that prosperity could be found there. Chinese railroad workers further added to the diversity of the region’s population. Settlement from the East transformed the Great Plains. The huge herds of American bison that roamed the plains were virtually wiped out, and farmers plowed the natural grasses to plant wheat and other crops. The cattle industry rose in importance as the railroad provided a practical means for getting the cattle to market.

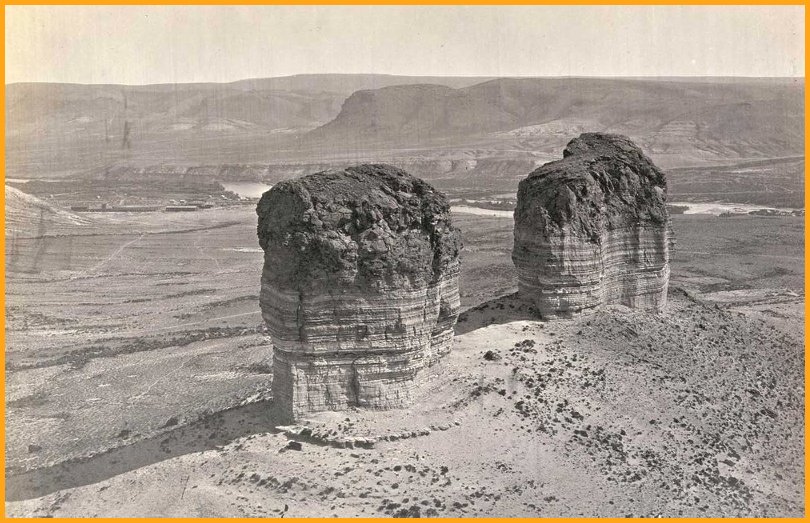

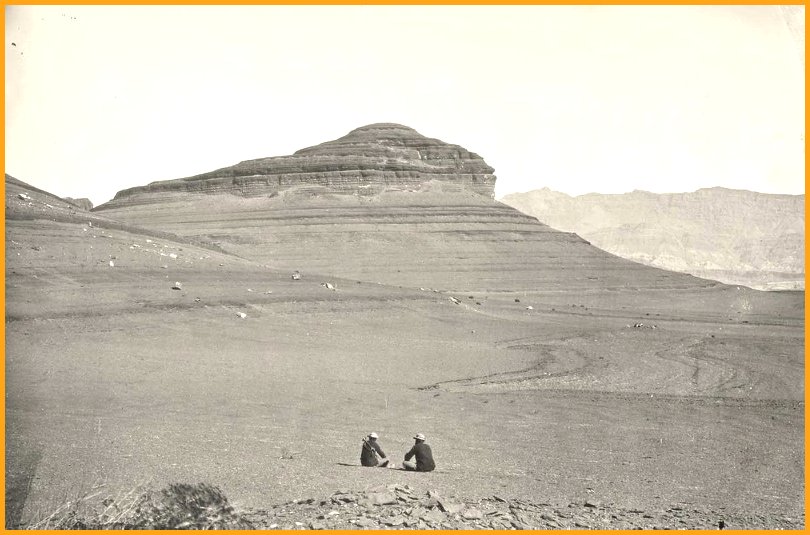

Twin buttes stand near Green River City, Wyoming, photographed in 1872.

The loss of the bison and growth of white settlement drastically affected the lives of the Native Americans living in the West. In the conflicts that resulted, the American Indians, despite occasional victories, seemed doomed to defeat by the greater numbers of settlers and the military force of the U.S. government. By the 1880s, most American Indians had been confined to reservations, often in areas of the West that appeared least desirable to white settlers. The cowboy became the symbol for the West of the late 19th century, often depicted in popular culture as a glamorous or heroic figure. The stereotype of the heroic white cowboy is far from true, however. The first cowboys were Spanish vaqueros, who had introduced cattle to Mexico centuries earlier. Black cowboys also rode the range. Furthermore, the life of the cowboy was far from glamorous, involving long, hard hours of labor, poor living conditions, and economic hardship. The myth of the cowboy is only one of many myths that have shaped our views of the West in the late 19th century. Recently, some historians have turned away from the traditional view of the West as a frontier, a “meeting point between civilization and savagery” in the words of historian Frederick Jackson Turner. They have begun writing about the West as a crossroads of cultures, where various groups struggled for property, profit, and cultural dominance.

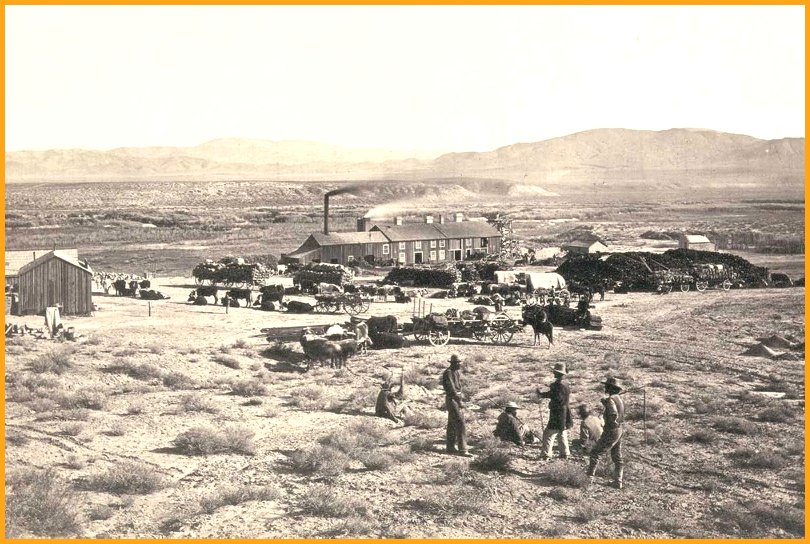

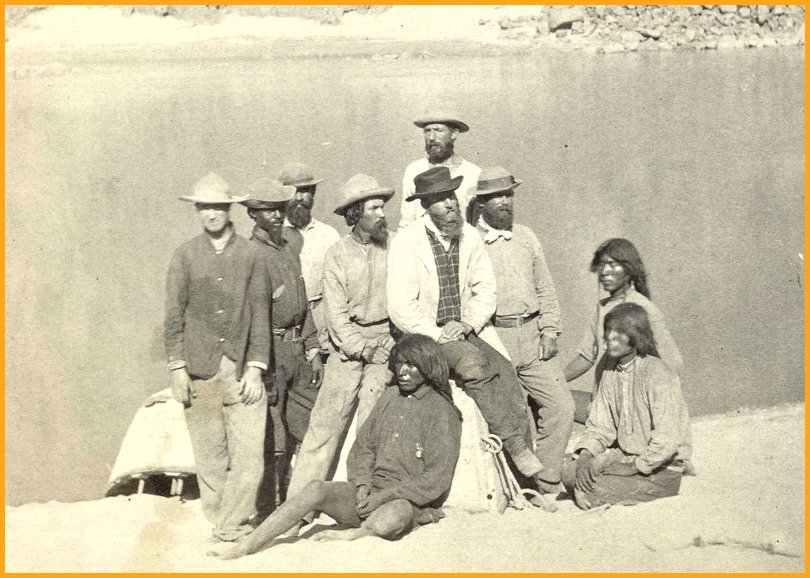

Members of Clarence King’s Fortieth Parallel Survey team, near Oreana, Nevada, in 1867.

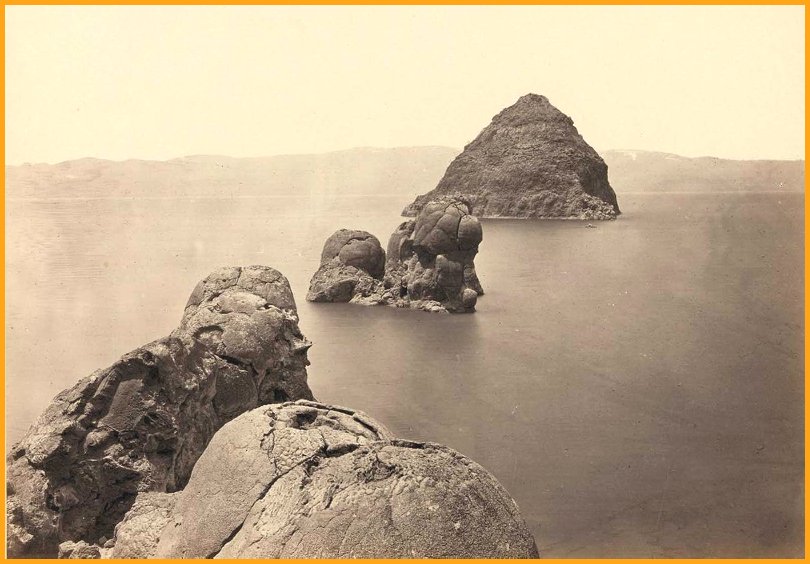

The Pyramid and Domes, a line of dome-shaped tufa rocks in Pyramid Lake, Nevada, seen in 1867.

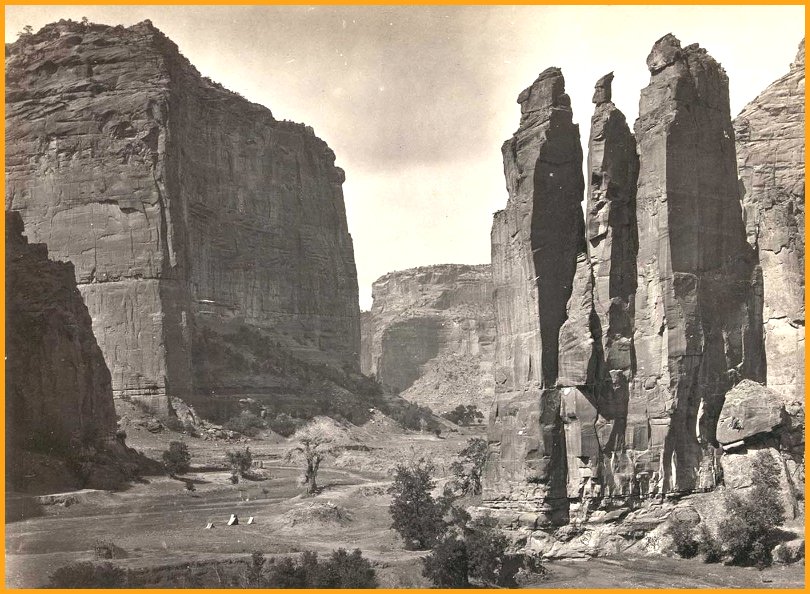

Panoramic view of tents and a camp identified as “Camp Beauty”, rock towers and canyon walls in Canyon de Chelly National Monument, Arizona. Tents and possibly a lean-to shelter stand on the canyon floor, near trees and talus. Photographed in 1873.

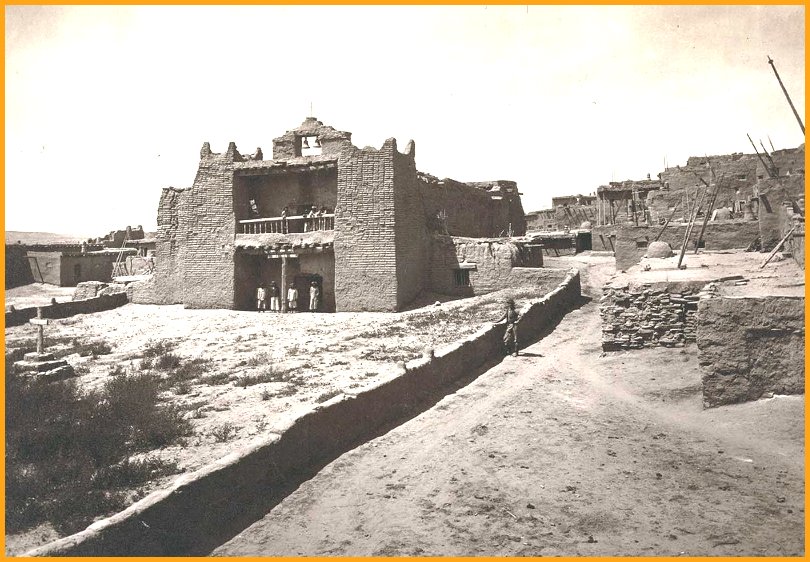

Old Mission Church, Zuni Pueblo, New Mexico. View from the plaza in 1873.

Boat crew of the “Picture” at Diamond Creek. Photo shows photographer Timothy O’Sullivan, fourth from left, with fellow members of the Wheeler survey and Native Americans, following ascent of the Colorado River through the Black Canyon in 1871.

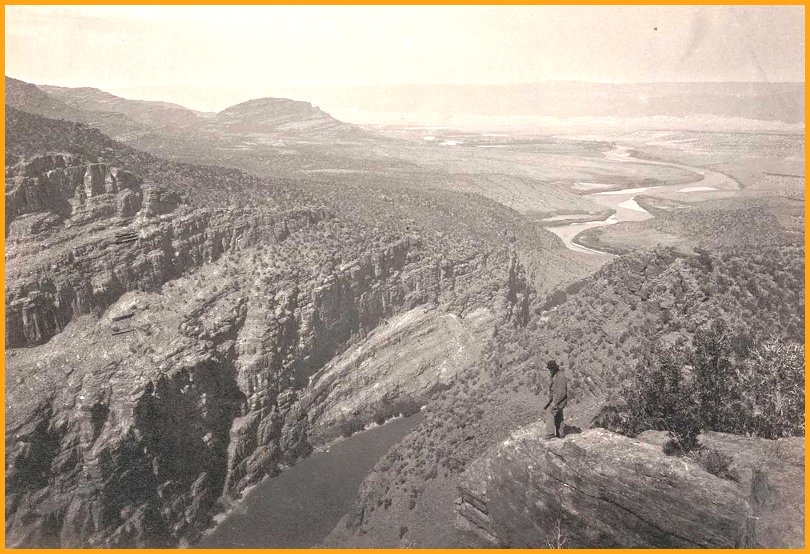

Browns Park, Colorado, 1872.

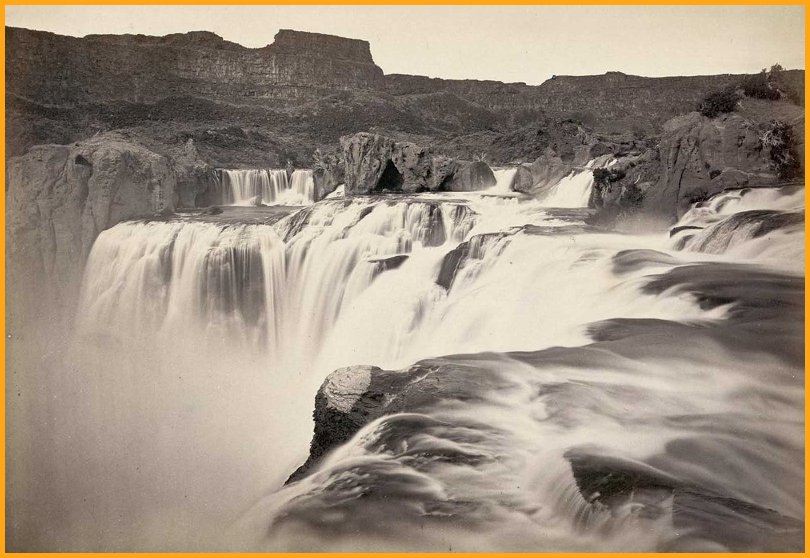

Shoshone Falls, Snake River, Idaho. A view across top of the falls in 1874.

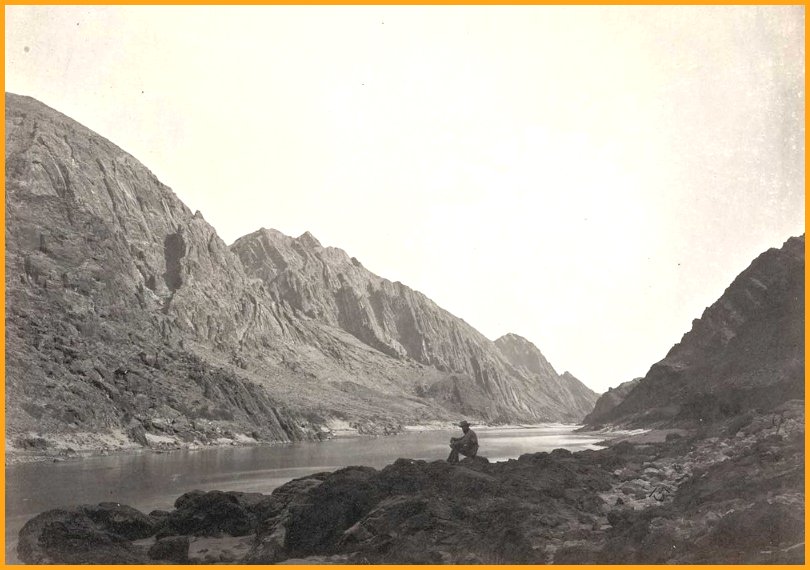

A man sits on a rocky shore beside the Colorado River in Iceberg Canyon, on the border of Mojave County, Arizona, and Clark County, Nevada in 1871.

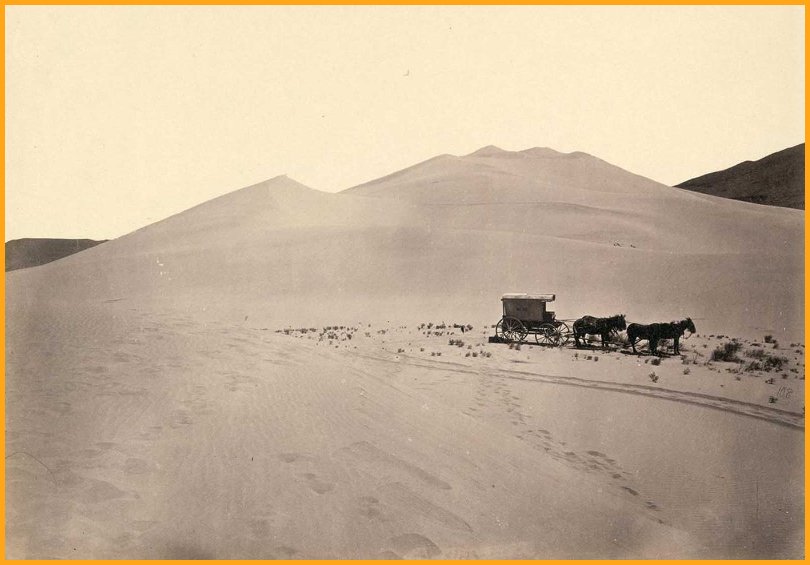

Timothy O’Sullivan’s darkroom wagon, pulled by four mules, entered the frame at the right side of the photograph, reached the center of the image, and turned around, heading back out of the frame. Footprints lead from the wagon toward the camera, revealing the photographer’s path. Photo taken in 1867, in the Carson Sink, part of Nevada’s Carson Desert.

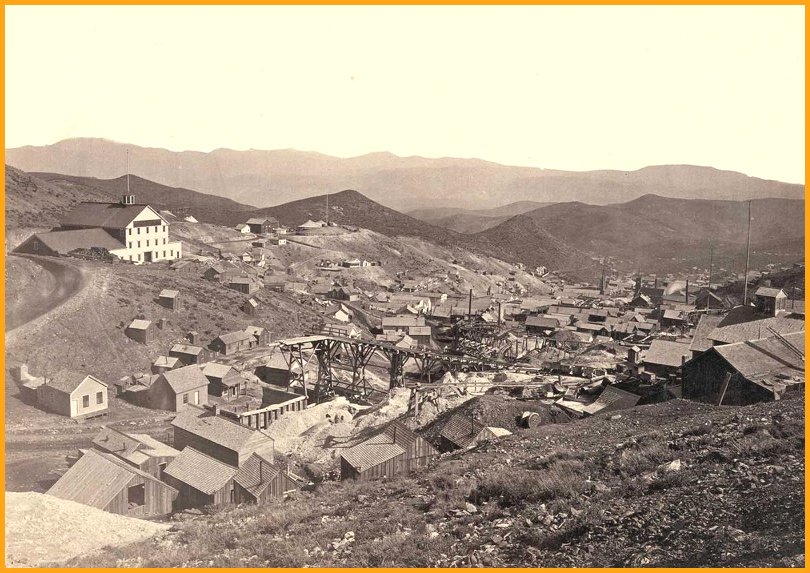

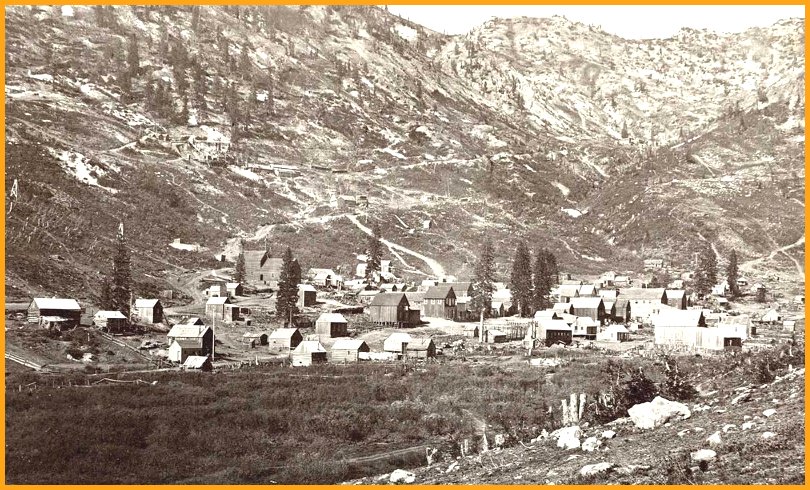

The mining town of Gold Hill, just south of Virginia City, Nevada, in 1867.

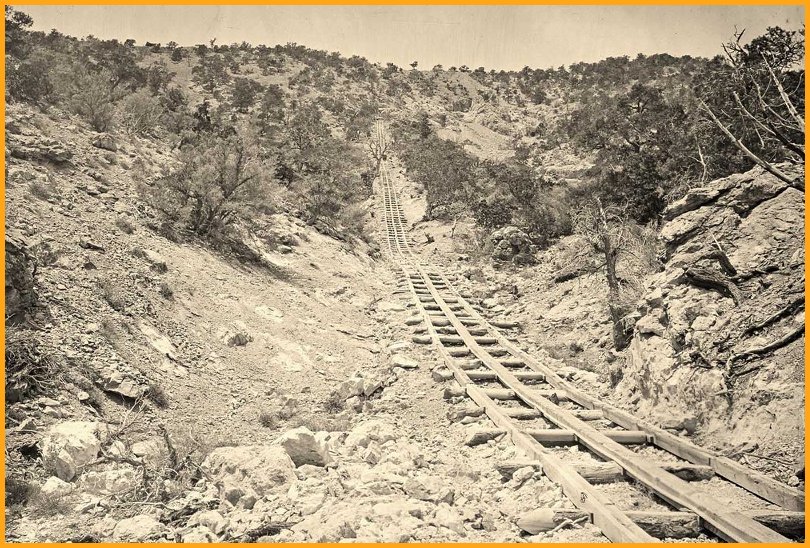

A wooden balanced incline used for gold mining, at the Illinois Mine in the Pahranagat Mining District, Nevada in 1871. An ore car would ride on parallel tracks connected to a pulley wheel at the top of tracks.

In 1867, O’Sullivan traveled to Virginia City, Nevada to document the activities at the Savage and the Gould and Curry mines on the Comstock Lode, the richest silver deposit in America. Working nine hundred feet underground, lit by an improvised flash — a burning magnesium wire, O’Sullivan photographed the miners in tunnels, shafts, and lifts.

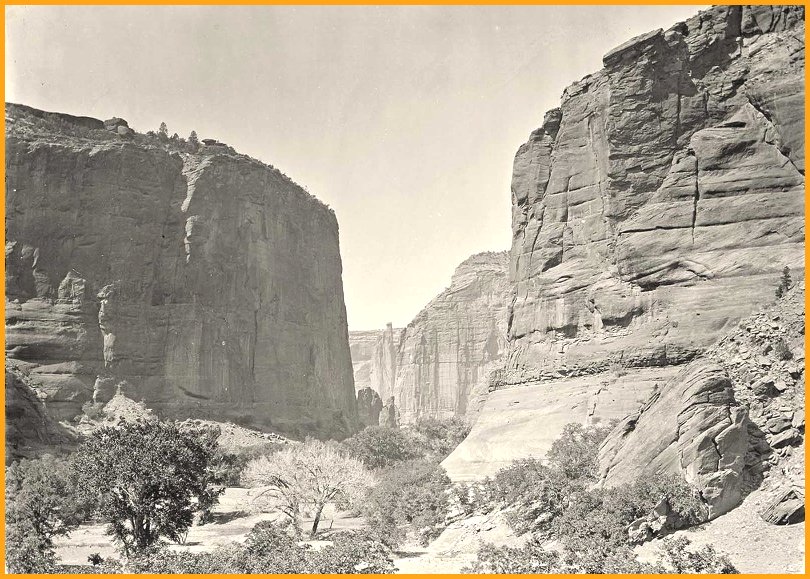

The head of Canyon de Chelly, looking past walls that rise some 1,200 feet above the canyon floor, in Arizona in 1873.

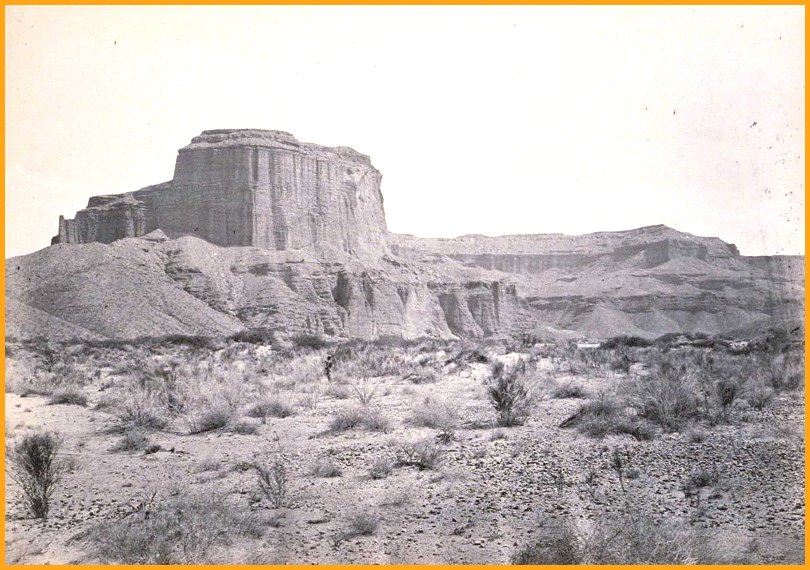

Headlands north of the Colorado River Plateau, 1872.

Native American (Paiute) men, women and children sit or stand and pose in rows under a tree near probably Cottonwood Springs (Washoe County), Nevada, in 1875.

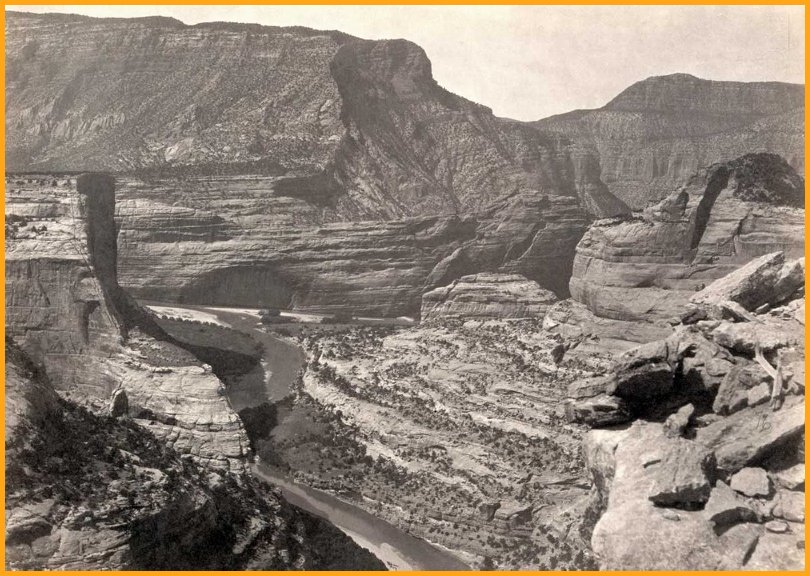

The junction of Green and Yampah Canyons, in Utah, in 1872.

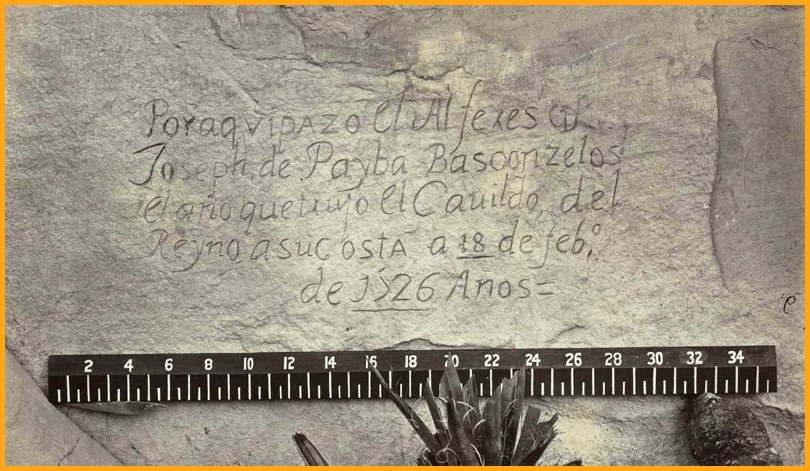

Nearly 150 years ago, photographer O’Sullivan came across this evidence of a visitor to the West that preceded his own expedition by another 150 years — A Spanish inscription from 1726. This close-up view of the inscription carved in the sandstone at Inscription Rock (El Morro National Monument), New Mexico reads, in English: “By this place passed Ensign Don Joseph de Payba Basconzelos, in the year in which he held the Council of the Kingdom at his expense, on the 18th of February, in the year 1726”.

Aboriginal life among the Navajo Indians. Near old Fort Defiance, New Mexico, in 1873.

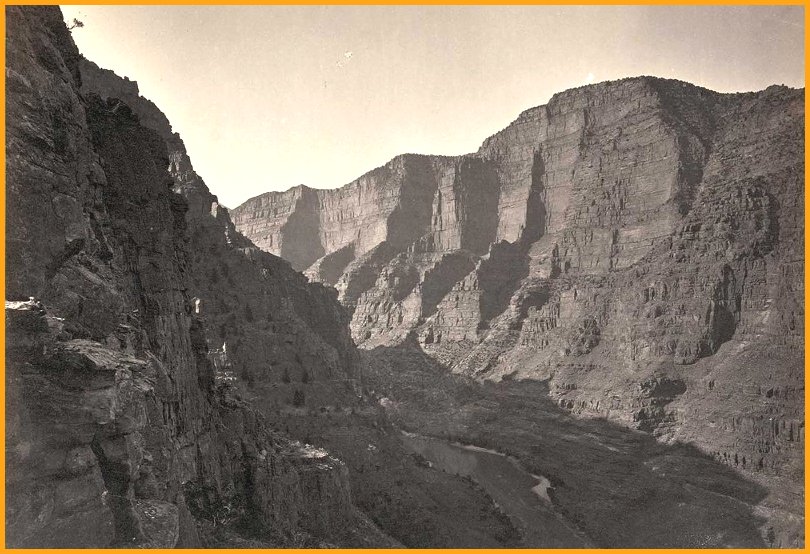

The Canyon of Lodore, Colorado, in 1872.

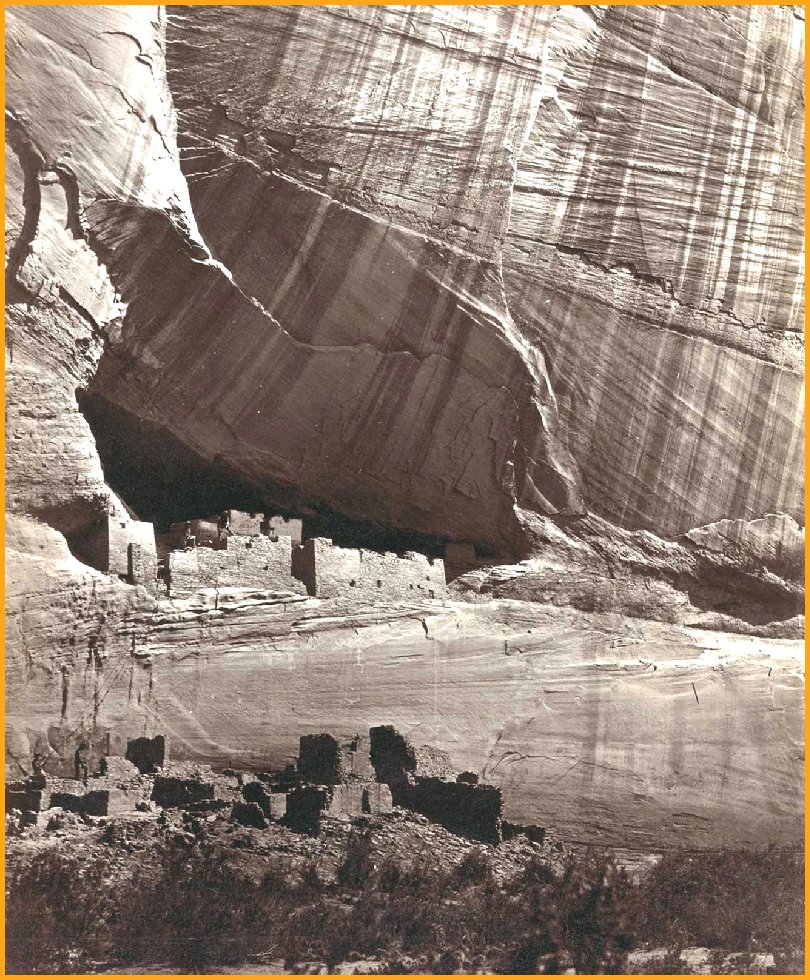

View of the White House, Ancestral Pueblo Native American (Anasazi) ruins in Canyon de Chelly, Arizona, in 1873. The cliff dwellings were built by the Anasazi more than 500 years earlier. At bottom, men stand and pose on cliff dwellings in a niche and on ruins on the canyon floor. Climbing ropes connect the groups of men.

The “Nettie”, an expedition boat on the Truckee River, western Nevada, in 1867.

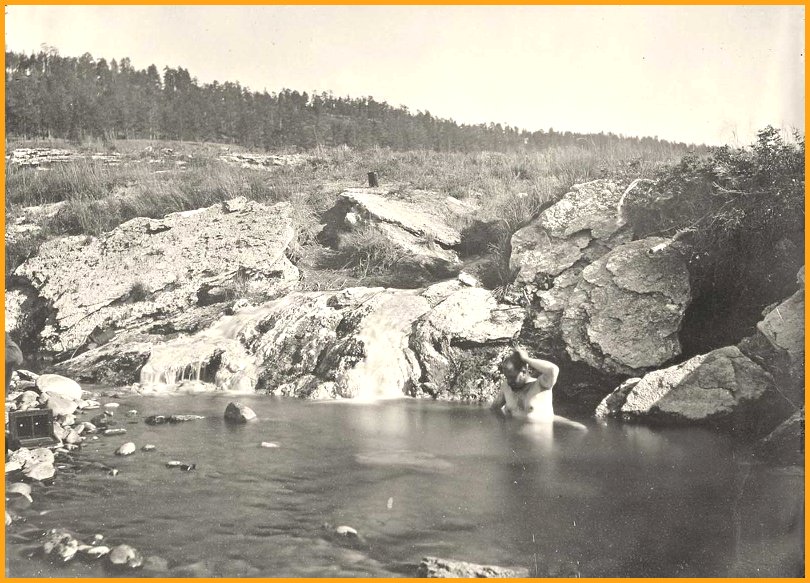

Man bathing in Pagosa Hot Spring, Colorado, in 1874.

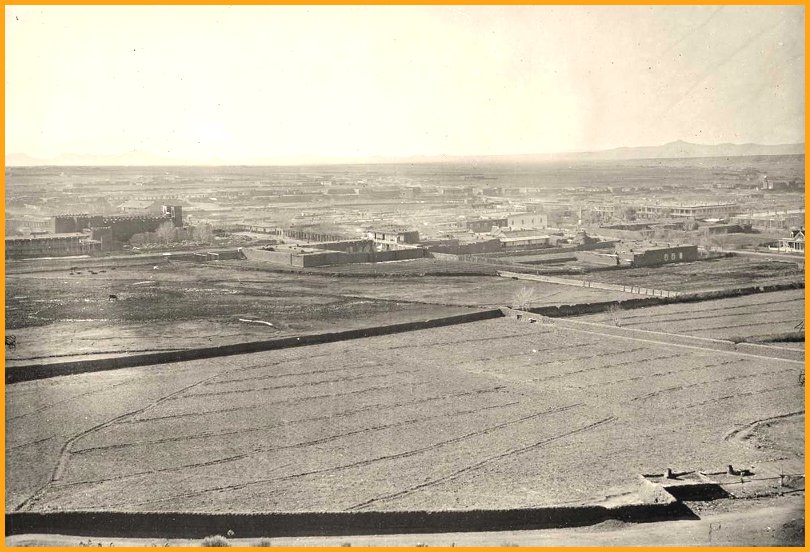

A distant view of Santa Fe, New Mexico in 1873.

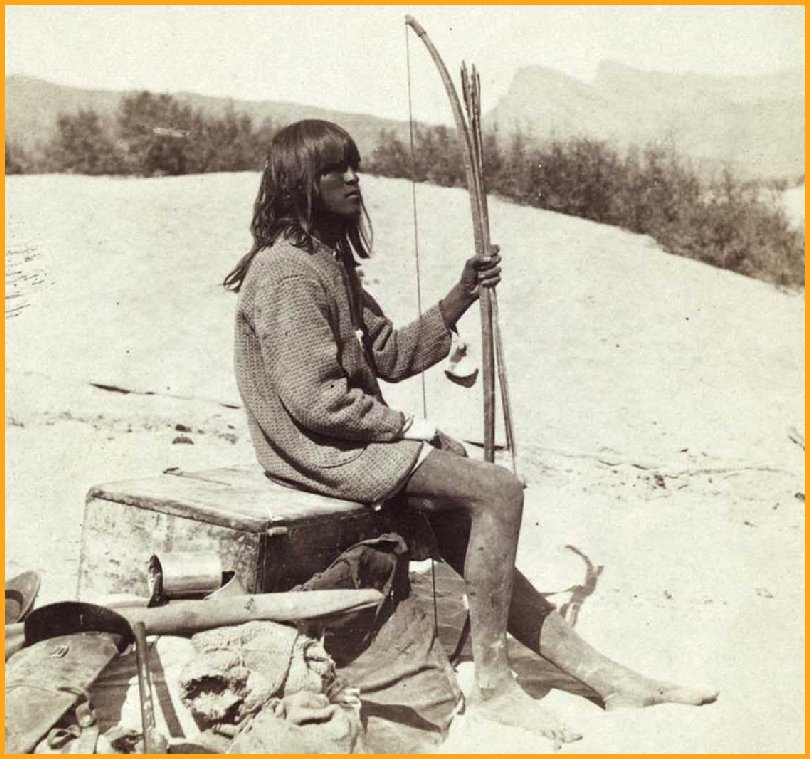

Maiman, a Mojave Indian, guide and interpreter during a portion of the season in the Colorado country, in 1871.

Alta City, Little Cottonwood, Utah, ca. 1873.

Cathedral Mesa, Colorado River, Arizona, 1871.

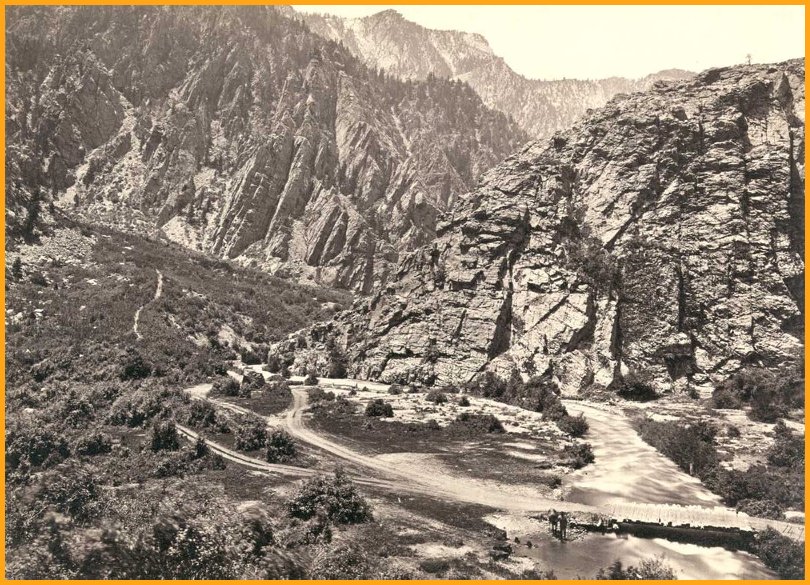

Big Cottonwood Canyon, Utah, in 1869. Note man and horse near the bridge at bottom right.

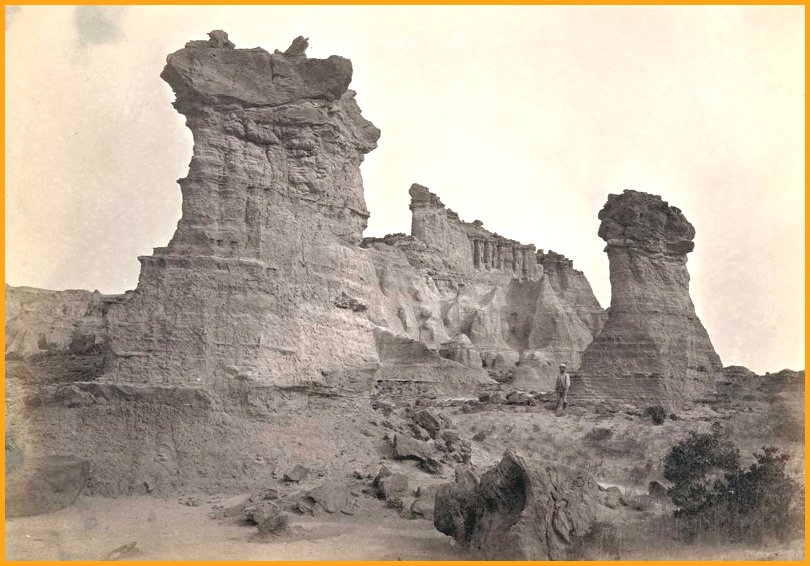

Rock formations in the Washakie Badlands, Wyoming, in 1872. A survey member stands at lower right for scale.

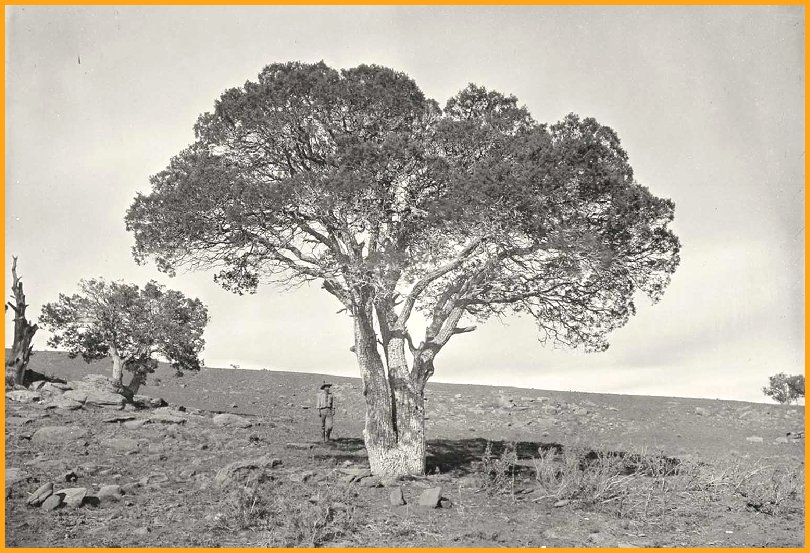

Oak Grove, White Mountains, Sierra Blanca, Arizona in 1873.

Shoshone Falls, Idaho, in 1868. Shoshone Falls, near present-day Twin Falls, Idaho, is 212 feet high, and flows over a rim 1,000 feet wide.

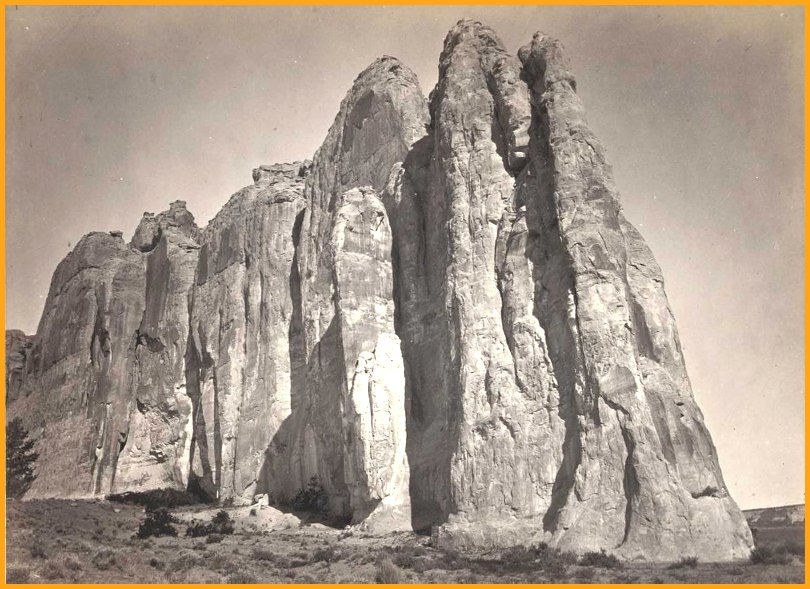

The south side of Inscription Rock (now El Morro National Monument), in New Mexico in 1873. Note the small figure of a man standing at bottom center. The prominent feature stands near a small pool of water, and has been a resting place for travelers for centuries. Since at least the 17th century, natives, Europeans, and later American pioneers carved names and messages into the rock face as they paused. In 1906, a law was passed, prohibiting further carving.